Principle #3: Be Proactive, Not Reactive

Focus on what you can control.

Quick note: for new subscribers, welcome! Today’s post is the third principle in a series of posts on my 7 Principles of Great Product Teams. You can read Principle #2 here.

My surname name is ‘Shackleton’ so I grew up with stories of Sir Ernest Shackleton who was a famous arctic explorer. I’ve always felt a strange kinship and a slightly unhealthy obsession with these stories of adventure.

One of the last great earthly explorations was the race to the South Pole. In 1911, two arctic explorers, Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen, led separate expeditions attempting to be come the first to reach the pole. They aimed to cover over 1500 miles in some of the toughest conditions on earth. I won’t belabor this point, but this was an incredibly ambitious and dangerous expedition in those days.

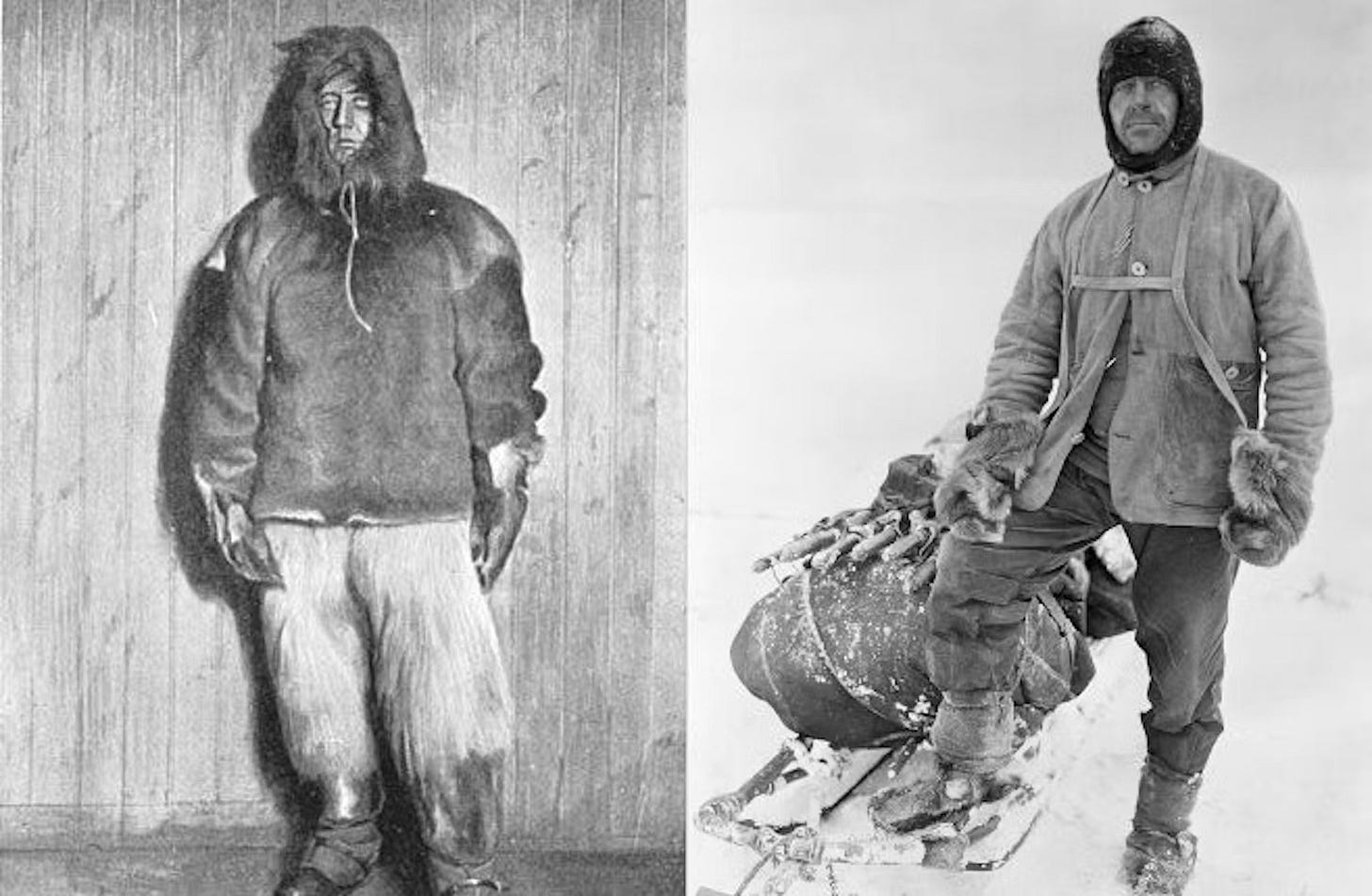

Photo: Amundsen in furs (left) in comparison to Scott's gear (right). (Photo by Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation)

To complete the journey, arctic explorers were forced to raise money, recruit teammates, and prepare for the dangerous journey.

Amundsen prepared vigorously and proactively. He recruited champion skiers, skillful sled dog drivers, and experienced carpenters. Before the journey, he proactively assessed whether the team would be compatible with each other for the long journey. He designed the team’s ski boots himself and tested them for over two years. Amundsen modified the expedition team’s clothes to learn from indigenous people of northern Greenland who wore sealskin and reindeer skin to combat the harsh conditions. He brought a library of 3,000 books and lots of musical instruments to prevent boredom and maintain morale during the dark winter months. He laid supply depots at predictable intervals in advance of a longer push to the pole. He was proactive in every aspect of preparation. He was proactive in finding proven solutions to future problems before they arose. He proactively sought out a new route that provided several advantages over the established route. On the journey itself, Amundsen’s team traveled the same distance each day, making steady progress regardless of the weather.

By contrast, Scott ordered expensive, mechanized motor sledges, which were largely untested before the journey. Early in the expedition, these mechanized motor sledges broke down under the conditions. He established fewer supply depots that were spaced further apart. His team took an approach of reacting to the weather, making long arduous pushes on good weather days and staying put on bad weather days.

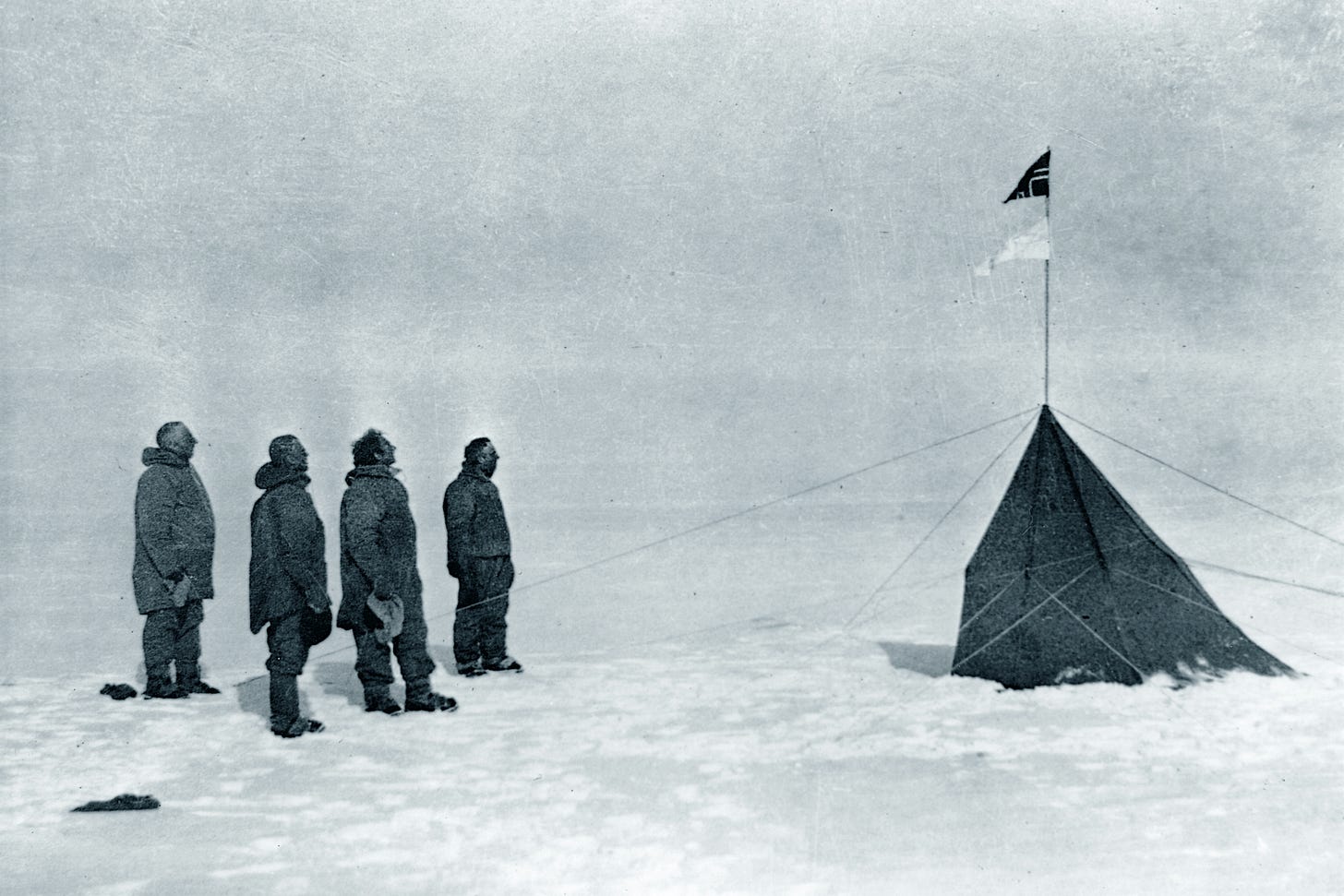

Photo: Amundsen's South Pole expedition at the pole. (Photo by Amundsen, Roald: The South Pole, Vol. II, first published by John Murray)

In the end, Amundsen’s proactive approach proved the difference. His team reached the South Pole first and returned safely. Scott, after a series of unfortunate circumstances, perished along with his companions.

Which team would you rather be on?

Creating a proactive operating mindset

Great product teams operate with a proactive mindset. They figure out what their team needs, and get ahead of it. They learn what customers need next. They admit when they were wrong, and change course. They find problems before they impact customers. And they look for ambiguity, with the intent to clarify.

To do so, they focus on what they can control. If they find themselves in a reactive mode, they reflect, change their systems and get back into a proactive mode. If you want to figure out if your team is in proactive mode vs reactive, just do a quick inventory of how each person is spending their time. If each person is feeling behind or pulled around by other people’s priorities, it’s likely time to make a change.

If I had to root cause a team moving slowly, more than half the time it’s just that they are caught in a reactive tailspin. They are getting pulled around by other people’s opinions and priorities instead of focusing on what they can control and being proactive.

Creating proactive, early feedback loops.

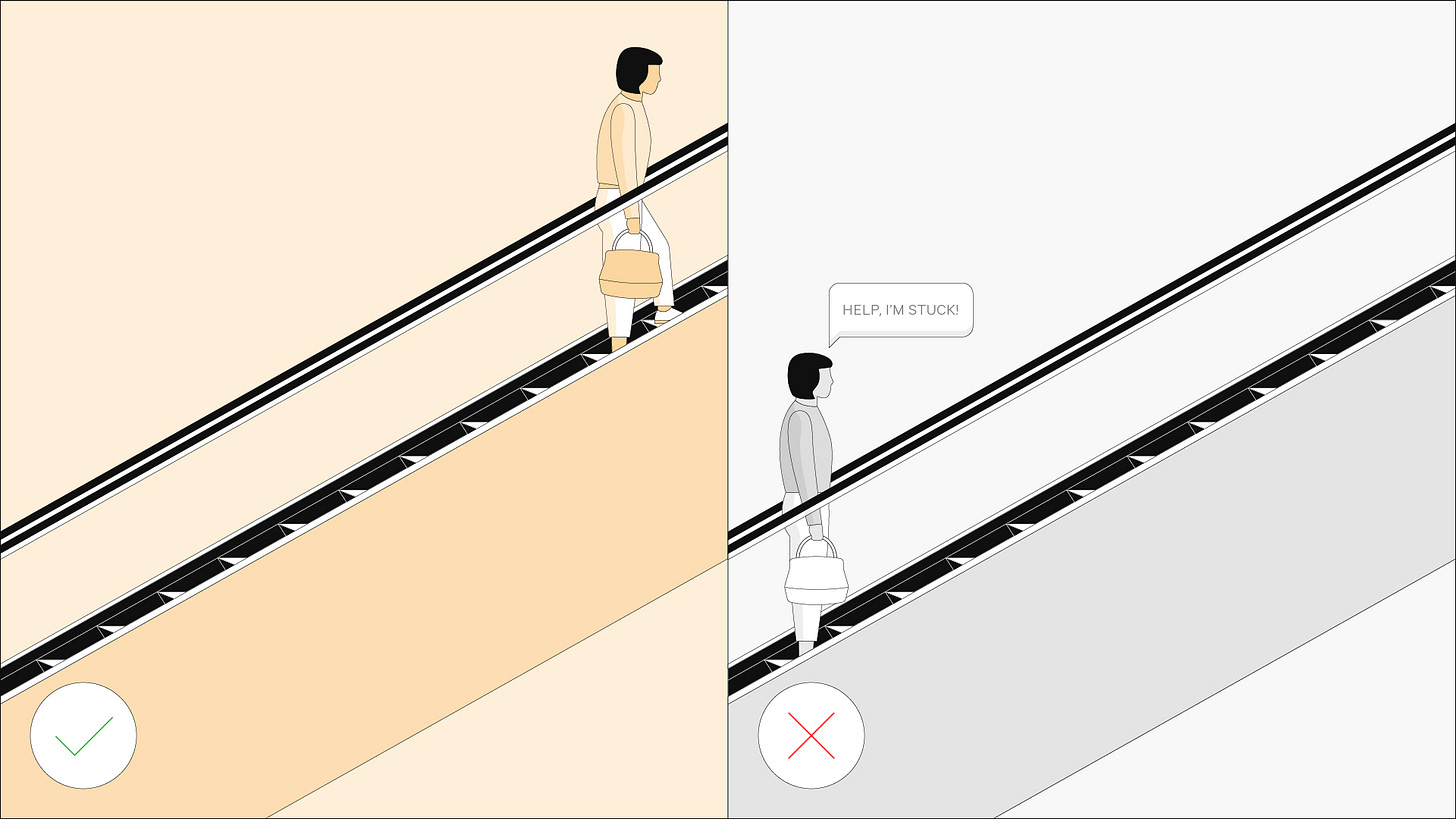

One way I encourage product managers at Coda to be proactive is to kick off their teams well. There are two parts to this. First, and this seems obvious but is often neglected, hold a kickoff meeting where the group shares any and all important context for the effort. There will be lots of unknowns, but it’s essential that the team starts on the same page. Second, form a braintrust that can help you and gather their input early.

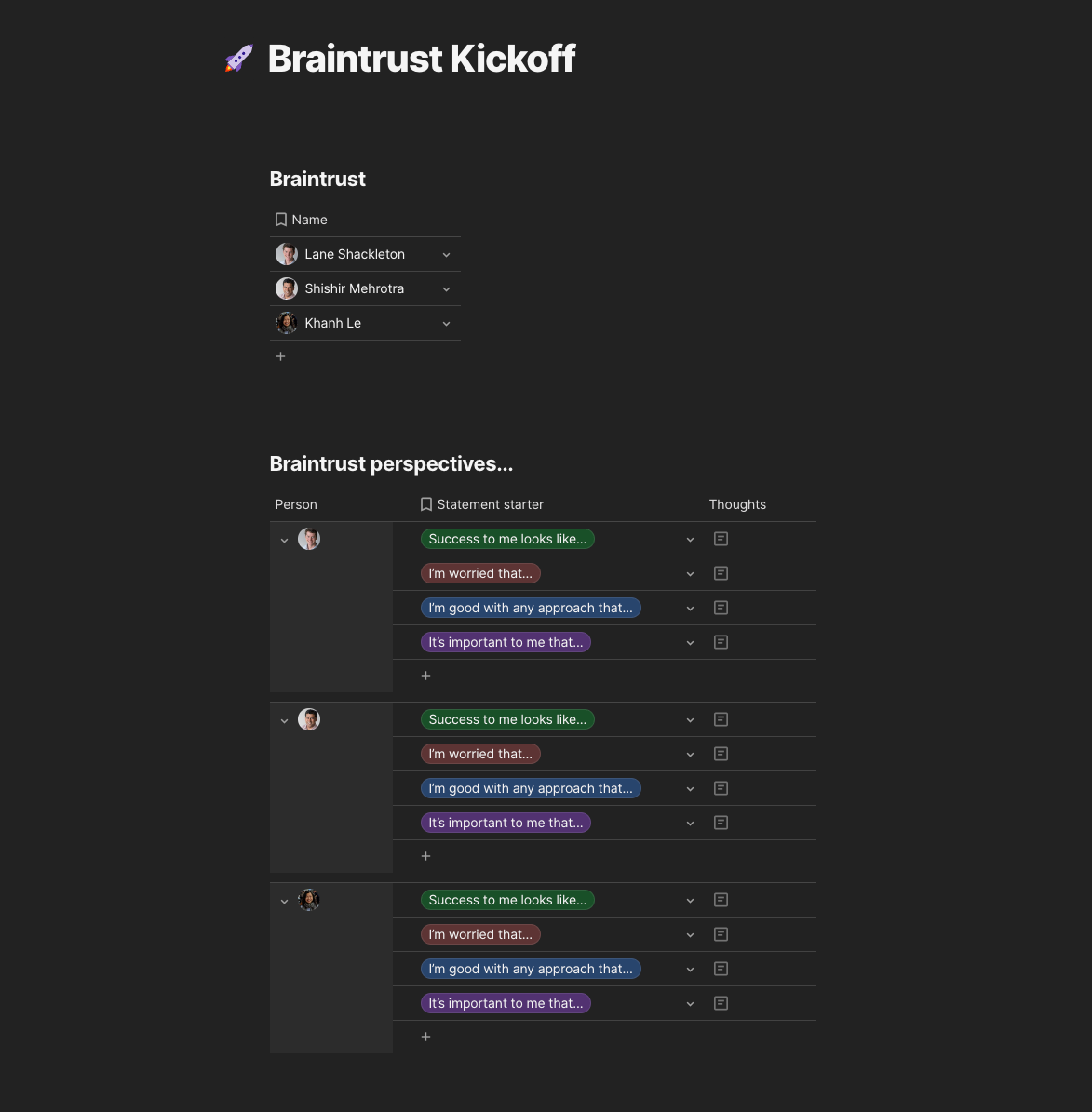

We use a braintrust concept inspired by Pixar where three to six people help provide timely feedback and help the team succeed. The key principle for the braintrust is to ‘add lift, not drag.’ A healthy braintrust can help accelerate teams toward the impact they are trying to make. I can’t tell you how valuable it is to gather the fears, implicit success criteria, and other early thoughts from your braintrust. It pre-empts so much downstream frustration to gather this up front and address it through the product development process instead of later when the team has spent a lot of time planning or building. For example, a key stakeholder might bring up a significant concern with a proposed product direction only after the team has prototyped or built the feature. Often, cases like this can be pre-empted by prompting those stakeholders early for their worries or unsaid expectations of success. As a PM, I’d rather know everyone’s context so that I can work within those constraints and challenge them early if needed.

Here is the braintrust kickoff template we use, feel free to copy it and customize it for your team.

Want more examples? Below are some sample statements you might hear from a reactive product team vs a proactive product team.

Customers

Reactive: ‘Let’s launch and wait to hear the feedback, then decide how to iterate.’

Proactive: ‘Before the alpha, let’s create a clickable prototype and show it to ten customers, so that we can start learning while we’re building the alpha.’

Strategy

Reactive: ‘We have to give an executive update, let’s review our strategy for that group.’

Proactive: ‘We’ll have a monthly strategy reflection, where we review progress and make adjustments based on what we’ve learned.’

Execution

Reactive: ‘Let’s review what got done on Friday.’

Proactive: ‘If you’re blocked on anything, please raise it immediately. Additionally, we’ll update progress in X location.’

Launches

Reactive: ‘We’re approaching launch day, let’s get ready to listen closely and address issues.’

Proactive: ‘Our alpha with 10 customers went well, the beta with 100 customers exposed 23 issues that we’ve fixed. We’ve tested our messaging strategy with key stakeholders. We feel confident and ready for a broader rollout. The detailed run of show leading up to the launch can be found here.’

Onboarding

Reactive: ‘This Twitter user reported that our onboarding is broken.’

Proactive: ‘It’s Jane’s turn in the rotation for our onboarding walkthrough, and she found one issue that needs to be addressed immediately.’

OKR & Goal Updates

Reactive: ‘We have to update this damn presentation every quarter with our progress.’

Proactive: ‘Our goal and OKR updates are sent out automatically to key stakeholders based on the updates we provide in our weekly meeting.’

Putting it into practice

Here are three more ideas for how your team can put this principle into practice.

(a) Run a pre-mortem on an upcoming launch.

One great way to be proactive is to look ahead to what problems may arise. Shreyas Doshi has a great doc that details how you might run an exercise with your product team to identify issues with launches and product efforts early so that you can mitigate them.

(b) Be proactive in addressing lessoned learned.

Ross Mayfield, a Product Lead at Zoom, shared the ritual he uses to proactively review where do double down and what to do differently. This is a great exercise to run once a quarter with your team. It’s similar to a ritual teams at Coda use, called ‘Stop, Start, Continue,’ where we review what to stop doing, what to start doing and what to continue doing.

(c) Ask your teammates or braintrust to red team your strategy.

A red team is a designated set of people that act as a competitor (or other external party). If you want to effectively put a strategy to the test, it can be helpful to run an exercise where a few people to put themselves in the mindset of a competitor, and game out how they may react to a given strategy. The goal of this exercise is to make your team’s strategy more robust by having it questioned and countered by people outside your immediate team. It’s a simple way to proactively counter strategy groupthink and test previously accepted assumptions.

Next

In the coming weeks, I’m excited to publish principles 4-7. Would love to hear your feedback too!

👋 This little newsletter experiment is just getting started. So if you enjoyed this post, I’d love it if you subscribed and shared with a friend. Have a wonderful day! ✌️

Note: also published on the Coda blog.